Your guide to Erb’s palsy.

We have years of experience with Erb’s palsy. Here we explain what you need to know.

We’re here to help you understand Erb’s palsy.

Causes. Symptoms. Treatment. Whatever you need to know, we’ve got you covered.

Erb’s palsy is a type of brachial plexus injury (nerve injury) that can occur in babies during childbirth. It affects movement and feeling in the arm.

Depending on the causes of Erb’s Palsy and the severity of the injury, it could be a temporary or permanent condition.

Understanding brachial plexus injury

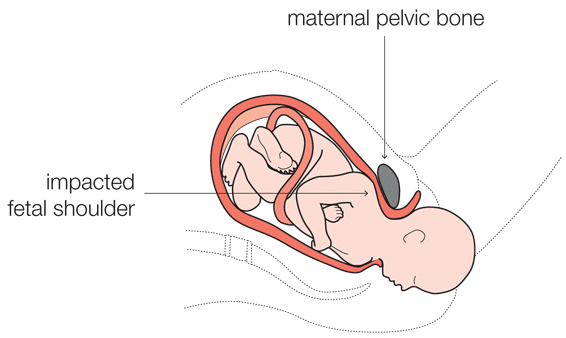

Here you can discover more about the brachial plexus nerves and the risk of injury when shoulder dystocia occurs during childbirth. This is when a baby’s shoulder gets stuck against the mother’s pelvis after the head is delivered, and additional help is required to release it.

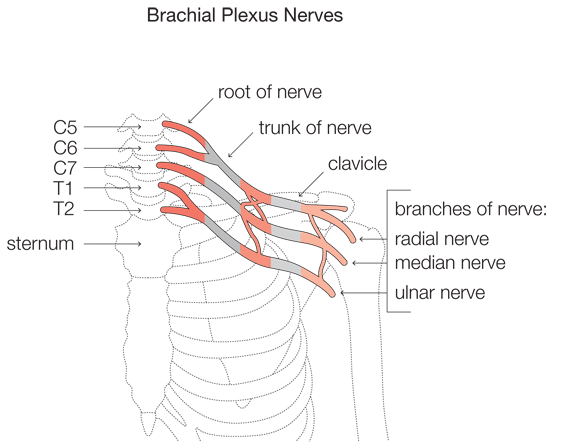

The brachial plexus is a network of nerves that emerge from the spinal cord through the vertebrae (neck bone) before passing under the collarbone to distribute down the arm. They become the major nerves controlling movement and feeling in the shoulder, elbow, wrist and hand.

They emerge from the vertebrae as four cervical nerve roots, referred to as C5, C6, C7 and C8 and the first thoracic nerve root (T1). These roots then combine to form three trunks:

- Nerves C5 and C6 form the upper trunk

- C7 forms the middle trunk

- C8 and T1 form the lower trunk.

As the trunks pass under the collarbone they split into anterior and posterior divisions and then into lateral, posterior and medial cords. The nerves that extend to the arm arise from these cords, including the musculocutaneous, axillary, radial, median and ulnar nerves.

These nerves are made up of thousands of fibres responsible for carrying electrical messages between the brain and the muscles. If these nerve fibres are damaged, the flow of messages from the brain are weakened or disrupted, and this can stop the corresponding muscles from working properly, if at all.

Type and extent of nerve damage

The symptoms and severity of Erb’s palsy can vary depending on which nerve(s) in the brachial plexus are damaged and whether they are stretched, torn (ruptured) or severed from the spinal cord (avulsed).

Damage to the baby’s upper trunk (nerve roots C5 and C6) is most common in brachial plexus injuries during childbirth. If the nerves are stretched or bruised (i.e. the injury is mild), they may heal themselves without treatment within a matter of months. This is the case in 90% of mild brachial plexus injuries to the upper trunk.

If all of the nerves in the group (C5 to T1) are damaged, then an entire shoulder, arm and hand may be paralysed. If this occurs, the child may also have associated Horner’s syndrome, characterised by a drooping eyelid and constriction of the child’s pupil. Surgery is required to repair the nerves, but few children will fully recover the use of their arm.

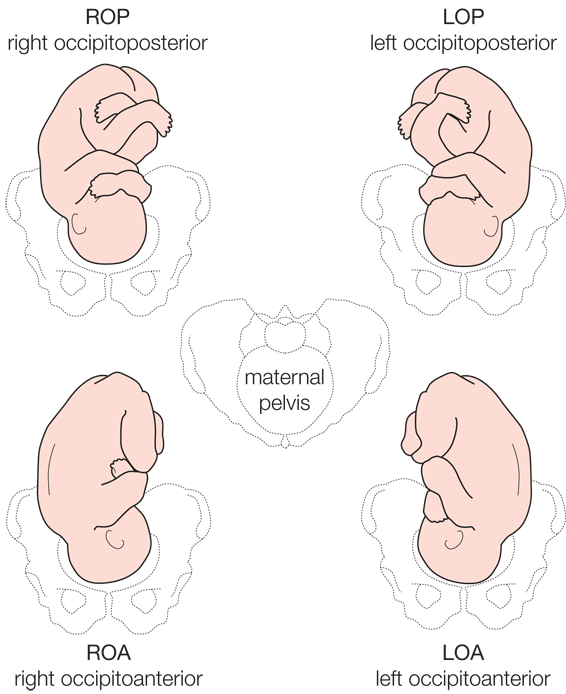

The importance of the baby’s position in shoulder dystocia

The shoulders can be stuck in either an anterior or posterior position. If the fetal shoulder is impacted in the upper pelvis against the mother’s pubic bone, it’s described as ‘anterior’. If the shoulder is impacted against the lower pelvis – the mother’s sacral promontory – it’s described as ‘posterior’.

If your child has suffered a brachial plexus injury during childbirth and you’re considering making a claim for medical negligence, it’s important to determine whether the affected shoulder was anterior or posterior at the time of delivery. It is easier to establish a claim when the affected shoulder was anterior . It is not impossible to succeed in a claim where the posterior shoulder is injured, but it is more difficult.

Frequently asked questions about the causes and severity of brachial plexus injury

Below we have put together the answers to common questions we receive from claimants in relation to the Erb’s palsy injury they or their child has suffered:

What factors are associated with brachial plexus injury during childbirth?

The nerves in the brachial plexus can be injured when a baby’s head, neck or shoulder is pulled or stretched during a difficult birth. Factors related to Erb’s palsy include:

- Shoulder dystocia (when the baby’s shoulder is stuck against the mother’s pelvis after the head has been delivered during a vaginal delivery)

- A difficult or prolonged labour

- Delivering a very large baby (in excess of 5 kg)

- Maternal diabetes

- A shoulder dystocia in a previous pregnancy

- Assisted vaginal delivery.

Incidences of brachial plexus injury occur most commonly in vaginal births with normal presentation. Very few incidences occur during breech or caesarean deliveries.

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists classify shoulder dystocia as: “a vaginal cephalic delivery that requires additional obstetric manoeuvres to deliver the fetus after the head has delivered and gentle traction has failed.”

Put simply, it’s the result of one or both of the baby’s shoulders getting stuck (impacted) against the mother’s pelvis after the head has been delivered.

Thankfully the incidence of shoulder dystocia occurring is relatively rare, but there are particular risk factors that may increase its chance, such as:

- A shoulder dystocia in a previous pregnancy

- A baby with an anticipated birth weight in excess of 5 kg

- Diabetic mothers with an anticipated baby weighing in excess of 4.5 kg.

A baby’s shoulder can become impacted when the mother’s pelvic opening is too small to allow for the baby’s shoulders to pass into the birth canal after the head has been delivered. This most commonly occurs with very large babies.

When shoulder dystocia happens, it’s a medical emergency for both mother and baby. Once the fetal head is delivered, the baby’s umbilical cord is likely to be compressed and delivery needs to happen quickly to avoid the baby suffering oxygen deprivation with the risk of brain damage and, at worst, death. For the mother, the risk of a post partum haemorrhage (excessive blood loss) is increased with an obstructed birth.

Once the baby’s head is delivered, the obstetrician or midwife should apply very gentle traction (pull) on the head to test for the progress of the rest of the body with the next contraction. A delivery is described as ‘obstructed’ when:

- There has been a slow and difficult delivery of the baby’s head

- There is no movement of the body towards delivery

- The baby’s head and neck retracts back into the uterus, called ‘turtle necking’

- After the baby’s head has been delivered, the head does not rotate back to restore its normal relationship with the shoulders to aid delivery (a process called restitution).

Once shoulder dystocia is diagnosed, midwives and obstetricians should follow set emergency procedures to release the shoulders (known as HELPERR). These include:

-

1

Immediately calling for additional help by pressing the emergency buzzer.

-

2

Placing the mother in the ‘McRoberts’ position. This is when mum is placed on her back and her legs are removed from stirrups. Two people are required to flex each of the mother’s leg backwards at the same time towards the mother’s head to widen the pelvis.

-

3

If Step 2 is not effective, while still in the McRobert’s position, a third person should apply suprapubic pressure by pressing down just above the maternal pubic bone in an effort to encourage the fetal shoulder to descend down into the pelvis and under the bone. Gentle traction in line with the baby’s body should be applied to deliver the baby.

-

4

If Step 3 is not effective, the mother could be placed in the ‘all fours’ position to help widen the pelvis.

-

5

If Step 4 fails, an episiotomy (cutting the vagina) will allow additional room for the obstetrician to place all of their hand into the vagina to either rotate the baby or to deliver its posterior arm. Both of these internal manoeuvres allow for the upper shoulder to be released and for the body to be delivered.

-

6

It is rare that the above manoeuvres fail to deliver the baby. Otherwise, the options are limited to:

• Breaking or bending the fetal clavicle to reduce the width of the baby

• Undertaking a symphysiotomy – a surgical procedure in which the cartilage of the pubic symphysis is divided to widen the pelvis

• Undertaking the Zavanelli manoeuvre where the fetus is pushed back up into the uterus to prepare for an emergency caesarean section.

Medical negligence claims for Erb’s palsy usually arise for two reasons:

- The mother should have been advised to undergo a caesarean section due to the risks of shoulder dystocia – or alternatively the various options for delivery are not discussed with the mother so that an informed decision can be made about mode of delivery

- The team delivering the baby failed to properly execute the emergency procedures and instead apply excessive traction and/or in inappropriate directions to the fetal head in an attempt to deliver the baby.

When shoulders are stuck, excessive pull on the baby’s head is known to cause damage to the brachial plexus nerves. The extent of damage is usually in relation to the force and angle of the pull.

Absence of adequate shoulder dystocia training

Growing evidence suggests that those who have had insufficient training on the management of shoulder dystocia are more likely to use excessive force when applying traction to the fetal head, carrying with it the risk of brachial plexus injury.

Poorly executed internal manoeuvres during delivery

Internal manoeuvres are very difficult to perform, especially if there has been inadequate training or the obstetrician is inexperienced.

Common internal manoeuvres that help to rotate the baby’s position and release the shoulders are the Woods’ screw manoeuvre and Rubins II. These manoeuvres require the midwife or obstetrician to insert their hands into the vagina to manipulate the baby’s position. They may also attempt to deliver the posterior arm first (to allow more space for the upper body to be delivered), but a frequent mistake is attempting to deliver the shoulder first, instead of the arm.

Good record keeping allows for a review of the birth if necessary and for lessons to be learned. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) has produced a pro-forma that should be completed in the event of shoulder dystocia. It clearly sets out all of the information required in the medical records to give an accurate account of the birth, including who was involved and exactly what procedures were taken to relieve the obstruction.

If a medical negligence claim is brought, these records become very important.

In establishing the cause of your baby’s brachial plexus injury and whether negligent handling was involved, it’s important to establish whether the baby’s shoulder was anterior or posterior at the time of delivery.

The significance of the baby’s position on delivery

It is accepted that when the baby is in a posterior position at the time of delivery, it is more difficult to prove that any injury to the shoulder is due to negligent handling by the midwife or obstetrician.

In the posterior position, the brachial plexus nerves can be stretched and injured when uterine contractions force the baby down against the bone and its shoulder is impacted against the mother’s sacral promontory.

It’s accepted that when the baby is in an anterior position at the time of delivery, any injury to the brachial plexus is much more likely to be caused by excessive traction (excessive pull) on the part of the midwife or obstetrician.

The excessive traction applied by the birth attendant can cause damage to the brachial plexus by:

- The extent of the force used

- The incorrect direction of force applied

- The nature of the force e.g. sudden jerking or pulling movements.

For further reference:

1. Mollberg, M., et al., Obstetric brachial plexus palsy: a prospective study on risk factors related to manual assistance during the second stage of labor. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, 2007. 86(2): p. 198-204

2. Mataizeau, J., C. Gayet, and F. Plenat, Les Lesions Obstetricales du Plexus Brachial. Chir Pediatr, 1979. 20(3):p. 159-163

The significance of a permanent injury

Temporary injuries to the brachial plexus can be caused by natural processes or by negligent handling during the birth. It’s generally considered, however, that permanent injuries to the nerves are caused by excessive and inappropriate traction by the birth attendant, significantly stretching the neck at such an angle to cause severe damage to the nerves.

Can the force of maternal contractions cause brachial plexus injury?

It’s not the force of the push or pull in itself that damages the brachial plexus nerves, but rather the stretching of the neck at an angle. With strong contractions, a temporary injury might occur if the baby is in a posterior position when its shoulders become impacted. But very strong contractions in themselves should not cause permanent nerve injury. To cause a severe and permanent injury requires force on a stretched neck, when the head is caused to extend at a significant angle to the neck.

It has been hypothesised that a very short second stage of labour (the pushing stage) may be related to brachial plexus nerve injuries but there does not appear to be clear evidence on this.

Recent case developments

On the back of a study prepared by Professor Tim Draycott, a recent Scottish case illustrates how the facts surrounding a birth may now speak for themselves in favour of the claimant.

In CD v Lanarkshire Acute Hospitals NHS Trust [2015] CSOH 142, Lady Rae concluded in her judgement:

“While I accept that the research currently available does not conclude that all brachial plexus injuries are necessarily the result of excessive traction in the face of shoulder dystocia, it is clear from the evidence of Professor Draycott and Professor Carlstedt that consideration has to be given to the nature and severity of the injury suffered by C, the fact that it was his anterior shoulder which was affected, as opposed to the posterior shoulder, and to the fact that the injury was permanent. When these factors are taken into account…it is more probably than not that the injury to C was caused by excessive traction in the context of shoulder dystocia.”

Professor Draycott’s published study found that at Southmead Hospital they had no incidences of permanent brachial plexus injury in 24,000 births as a result of appropriate staff training. He commented at the trial:

“This study showed that with intensive training… the incidence of permanent brachial plexus injury was reduced to nil.”

In Lady Rae’s judgment it was noted:

“Professor Draycott was of the view therefore that permanent injury is almost always avoidable and cannot be caused by the natural propulsion forces of birth because the process of labour has not changed…He specified other such factors such as: the injury to C involved damage to 3 nerve roots…it involved the anterior arm; and the injury was permanent. This all pointed to the injury being preventable and relating to poor management of shoulder dystocia.”

It now seems that if certain criteria are met, such as the baby lying in an anterior position on delivery and sustaining severe permanent injury to the brachial plexus, the claimant’s legal representative can argue with a greater degree of confidence that the injury, on balance, was caused by excessive traction to the fetal head. In these circumstances there would be less need for strong supporting witness statements evidencing the actions of those attending the birth.

Further reading:

Crofts, J. F et al., Can accurate training and management for shoulder dystocia prevent all permanent brachial plexus injuries? BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Vol. 120, 06.2013, p. 412-412

To help diagnose and treat brachial plexus injuries, various classifications exist. These classifications identify the nerves injured in the brachial plexus, the symptoms of the injury and the likelihood of recovery.

In the UK the primary classification system is the Narakas classification system (developed by A.O. Narakas in 1986).

The Narakas classification system

Group 1: Group 1 represents injury to the C5 and C6 nerve roots resulting in:

- Difficulty lifting the affected arm above the head (restricted shoulder abduction)

- Difficulty rotating the shoulder away from the body (restricted external rotation)

- Difficulty bending the elbow (restricted elbow flexion)

- Difficulty twisting the forearm so that the palm of the hand is facing forward (restricted forearm supination).

As a result, a person with brachial plexus injury may present with the affected arm hanging down by their side, straightened and rotated towards the body, and with the palm of the hand facing backwards in pronation.

90% of people with a group 1 injury will return to having normal function.

Group 2: Group 2 represents injury to the C5, C6 and C7 nerve roots. In addition to the difficulties experienced above, people in group 2 also have difficulty in bending the wrist back (wrist extension).

75% of people with a group 2 injury will return to having normal function.

Group 3: Group 3 represents injury to the C5, C6, C7 and C8 nerve roots. People in this group experience complete arm paralysis.

Less than 50% recover some satisfactory function.

Group 4: Group 4 represents injury to the C5, C6, C7, C8 and T1 nerve roots. In addition to arm paralysis, people in group 4 experience Horner’s syndrome. Horner’s syndrome describes damage to a bundle of nerves that are responsible for controlling some of the muscles of the eye. As a result, people with Horner’s syndrome have a constricted pupil and droopy eyelid.

Surgery is required to repair the nerves, but few children will gain full functional recovery.

A three-tiered classification system to describe the severity of nerve damage was developed by Sir Herbert Seddon in 1942. It’s called the Seddon classification and it helps professionals to offer a likely prognosis.

The Seddon classification system

Neurapraxia: This is the mildest type of peripheral nerve damage when the insulation around the nerve’s axon is damaged.

There is no damage to the axon itself, which is the part of the nerve fibre responsible for conducting electrical impulses to muscles.

This localised damage to the outer nerve fibres (the myelin sheath) causes an interruption in the conduction of the impulse down the axon resulting in short-term paralysis or muscle weakness.

Spontaneous recovery (remyelination) usually takes place within weeks to months.

Axonotmesis: This is more severe damage to the nerve fibres, where both the myelin sheath and the axon of the nerve are damaged but the Schwann cells and the connective tissue framework surrounding the axon (the endoneurium, perineurium and epineurium) remain intact.

Axonotmesis leads to Wallerian degeneration shortly after the injury. This is when the part of the axon between the injury and the neuron’s cell body starts to degenerate (including the myelin sheath), leaving only the outermost layer of the nerve fibre hollowed out.

When the degeneration is complete, regeneration of the axon can start from the lesion, typically within four days of the injury. New shoots grow at a pace of one millimetre per day.

The prognosis for axonotmesis is fair, but it may take months for the nerve to regrow and connect to the muscle. The process may be complicated by scar tissue forming at the site of the injury (known as neuroma). The scar tissue could interrupt the conduction of electrical impulses between the muscles and the nerve cell.

Neurotmesis: This is the most severe form of a nerve injury.

Here the axon, myelin sheath and connective-tissue framework are damaged. Electrical impulses cannot be sent to the muscles and the limb is paralysed. Wallerian degeneration will start following the injury (similar to axonotmesis) and this is when the part of the axon between the injury and the neuron’s cell body starts to degenerate. Unlike axonotmesis, the prognosis for regrowth is very poor.

Surgery may be able to repair the nerve so that some movement and feeling in the arm can be restored.

Professionals may also refer to Sunderland’s system (Sir Sydney Sunderland), which further divides Seddon’s neurotmesis classification into three subcategories.

- Neurotmesis (third degree) – the outer connective tissue framework surrounding the nerve fibres are intact/undamaged (the epineurium and perineurium), but the endoneurium is injured. This is the connective tissue that surrounds each individual myelinated axon. Spontaneous recovery is possible, but surgery may be required.

- Neurotmesis (fourth degree) – the perineurium and the endoneurium are injured and only the outer connective tissues (epineurium) remains intact. Only surgery can repair the nerve.

- Neurotmesis (fifth degree) – this is characterised by complete severance (transection) of the nerve trunk and recovery is not possible without surgery.

Symptoms of Erb’s palsy

If damage is primarily to the upper trunk of the brachial plexus (the C5, C6 nerve roots), symptoms of Erb’s palsy could include:

- Partial or complete paralysis of the arm depending on the extent of damage

- A limp, pronated arm (turned in) with wrist flexed back in the ‘waiter’s tip’ position

- Weak shoulder abduction (difficulty lifting the arm from the shoulder)

- Difficulty rotating the arm away from the shoulder (eg if putting your arm in a sleeve)

- Weak elbow flexion (difficulty bending the arm at the elbow)

- Pronated arm with palm facing down or back (no forearm supination enabling the palm to face up or out)

- Inability to regulate the temperature of the arm due to poor circulatory system

- Numbness / loss of sensation in areas of the affected arm

90 per cent of people with this type of injury will return to having normal function with the correct treatment.

If there is also damage to the C7 nerve root, symptoms will include the above and also:

- Difficulty extending the wrist (straightening the wrist or bending it away from the body)

72 per cent of people with damage affecting the C5, C6 and C7 nerve roots will return to having normal function with the right treatment.

If there is injury to the nerves of the upper, middle and lower trunk of the brachial plexus (C5, C6, C7, C8 and T1), symptoms will include:

- Complete paralysis of the shoulder, arm and hand

- Horner’s syndrome, characterised by a constricted pupil and droopy eyelid due to damage to a bundle of nerves responsible for controlling some of the muscles of the eye. This can happen when the lower trunk of the brachial plexus is avulsed (torn right away) from the spinal cord.

In these cases, surgery is required, but few children will gain full functional recovery if all five nerve roots are damaged.

Children showing the symptoms of Erb’s palsy may also experience associated weakness, paralysis and loss of sensation in their arm, including:

- Decreased grip in their hand due to weakness in the arm

- Associated torticollis – characterised by the baby’s head being held tilted to one side and the face turned to the look towards the other side. It is due to tightness of the muscle on one side of the neck.

- Trouble controlling movement in the arm, wrist and hand due to paralysis or muscle weakness

- A bent elbow because the joint is very tight (contracture of the elbow)

- Atrophy (deterioration) of the affected muscles in the arm

- Stunted growth in the affected shoulder, arm and hand

- Cramping, pain and discomfort (although not everyone with Erb’s palsy experiences this)

- Problems with their shoulder and shoulder pain due to weak muscles

- Loss of sensation, circulatory problems and the loss of the skin’s ability to heal means infections are common.

Damage to brachial plexus nerves is usually caused by an excessive pull on the baby’s head after it has descended, but when the shoulders are still in the uterus and stuck against the mother’s pelvic bone. This can cause the nerves to stretch or tear.

If the injury to the brachial plexus nerves is mild and primarily affects the upper and middle nerve trunks (C5, C6 and C7 roots) then it’s very possible for the damaged nerves to repair themselves shortly after birth. Healing can take up to three months and your paediatrician will perform regular tests to monitor any improvement.

If the injury is more severe and the nerve has been torn (ruptured) or, at worst, completely severed (avulsed) from the spinal cord, surgery will be required to recover any movement and sensation in the arm. The injury may be permanent.

It’s important to start physiotherapy for your baby as soon as Erb’s palsy has been identified and he/she has recovered from a traumatic birth. Physiotherapy cannot heal the nerves, but performing passive exercises on your baby can prevent muscles from deteriorating as the nerves begin to heal. It is also recommended before and after surgery if no self-healing occurs.

Can Erb’s palsy be treated?

Children who do have Erb’s palsy tend to adapt very well, much better than an adult would do if suddenly faced with the same issues, as they have adapted whilst growing up to find their own ways to do things.

However, certain jobs or tasks will be impossible for your child to perform (depending on the extent of the injuries). Often careers in the military or police may be excluded. There are existing treatments available to help ease your child’s specific difficulties though, and new and improved treatments are being developed all the time, including:

- Surgery – This treatment is not lifesaving, it does not have to be done, but often it offers a benefit. It is often time dependent; meaning you have to make a decision within a time frame, often before five or six months of age. There are other kinds of surgeries on the shoulder or arm which can be done at any time.

- Physiotherapy – To focus directly on strengthening the ‘core’ and shoulder girdle muscles which can improve postural alignment, range of movement, a reduction in arm length difference and a reduced risk of secondary complications. Find out more about physiotherapy, including the issues faced by people with erb’s palsy here.

- The development of a drug to help nerve recovery.

- The development of a new nerve graft with the child’s own cells.

- Training the body better to improve function and reduce pain.

In some cases, recovery can be helped by surgery.

It is difficult to be absolutely sure what recovery is going to be achieved over time and different medical and therapy teams around the world use different methods. It is then harder still to choose surgery and be sure it is going to improve upon what is likely to happen by natural recovery. This is why it is important to talk to your treating team and ask questions about what treatment is available and then talk through your teams’ answers with them to help you make the right decisions for your child. You must remember there are risks to any treatment but there are also risks of not having treatment.

It is always a difficult decision to make to undertake surgery on a child. We make decisions for our children all the time, but this one is often very stressful. The only advice experts can give to everyone is that you have to understand, from conversations with your treating team, what they think will happen if no surgery is undertaken and what the best case and worse case outcome from surgery will be. Then it is important to do your own reading and research, to make sure all your questions are answered before making any decision.

None of this surgery is lifesaving, it does not have to be done, but often it offers a benefit. This benefit for nerve surgery is often time dependent; meaning you have to decide within a time frame, often before five or six months of age. There are other kinds of surgeries on the shoulder or arm which can be done at any time and there is no time by which is has to be done.

At the Peripheral Nerve Injury Research Unit and the University College London Centre for Nerve Engineering they are working very hard on research into the way nerves heal. They are working towards:

- developing a drug to help nerve recovery

- how to detect which injuries will best benefit from surgery

- how to make a new nerve graft in the lab but with the child’s own cells, so we don’t have to take nerves from other part of the body to repair the injury.

- how to train the body better to improve function and reduce pain.

Organisations such as PROMPT are also engaged in supporting and teaching with midwives and obstetricians as the best cure for Erb’s palsy is prevention. If it does occur getting the right treatment as soon as possible is vital. It is important to continue to ensure that the profile of this injury is raised and education and information to be freely available to all, with early and clear pathways to referral for specialist help from a full team of trained experts. We try to play our part in that awareness raising and you can access various information webinars here which we have recorded with Trustees of the Erb’s Palsy Group, our clients and medical experts to highlight some of the everyday issues of living with erb’s palsy.

Daily life and therapy for Erb’s palsy

The restrictions on daily activities for an adult or child with Erb’s palsy depend upon the extent of the nerve injury and whether or not the affected limb is their dominant arm.

It may be easier for people with mild Erb’s palsy to develop ways to bathe, dress and prepare meals without much difficulty. But having more severe Erb’s palsy can significantly impair day-to-day activities, such as:

- Dressing

- Bathing

- Washing hair

- Preparing meals

- Driving

- Sport and hobbies.

Many of our clients are disabled to the extent that they require assistance to get dressed, particularly as children. As adults they may have adopted techniques enabling them to dress using only one arm or acquired clothing that’s easy to pull on and off.

Washing and drying hair can also prove difficult and tiring, particularly for women and girls with longer hair. Most women complain that they are unable to style their own hair because they cannot hold a hairbrush and hairdryer at the same time.

Preparing meals can be difficult for people with Erb’s palsy, as most food preparation requires the use of two hands. For example:

- Opening tins and packages

- Holding and cutting food

- Lifting heavy, hot trays out of the oven.

Driving a vehicle would be impossible without either using an automatic car or fitting adaptations to the car e.g. gear controls on the steering wheel or a specialist wheel that can be moved with only one limb.

For many people with Erb’s palsy, access to sport is difficult. This can be especially upsetting for children who might feel left out during school sports, particularly sports that require the use of upper limbs such as basketball and netball. Riding a bike is also difficult with one arm.

All schools should be able to include children with disabilities in their sporting activities and encourage everyone’s participation in team sports.

All mainstream schools and colleges will have special educational needs coordinators (SENCOS) and equality coordinators who can help to secure the services and additional help your child needs, even if they are not assessed as having special educational needs.

Occupational therapists give practical help and advice on carrying out everyday tasks that people with Erb’s palsy might struggle with. The aim is to ensure as much independence as possible whether at home or in the community.

For example, an occupational therapist can examine your home and routines, and advise on adaptations and equipment that might help in the kitchen or bathroom. They will also teach special techniques that can improve the performance of everyday tasks, especially self-care tasks such as eating, washing and dressing.

Therapists can also help in work or school settings by suggesting improvements to aid access and inclusion, including access to sports and aids for typing etc.

This help is vital for your – or your child’s – sense of belonging, independence and self-esteem.

It is a sad reality that people with significant physical disability, like moderate or severe Erb’s palsy, are excluded from applying for some of the more physically demanding roles within the police force, emergency services or armed forces. There are also some civilian roles that cannot be performed easily with an upper limb disability, including nursing, dentistry and manual labouring.

Many more jobs are, of course, possible with the right support from employers. Any office job, for example, would require your employer to undertake a careful ergonomic assessment of the desk and work area, and supply any special equipment required to assist with typing and using the phone etc.

Employers are encouraged by the Government to ensure equal access to work and to support disabled job applicants and employees.

Under the Equality Act 2010, employers have a duty to ensure disabled people can overcome any substantial disadvantages they may have by making ‘reasonable adjustments’ to working conditions. If you feel that reasonable adjustments have not been made, then you have a right to take your employer to an employment tribunal.

You may be eligible for the Government’s Access to Work programme to help pay for the cost of support at work. This could include special aids and equipment, office adaptations and support workers. If you are eligible, the department will approach both you and your employer for more information.

You can find out more about the ‘reasonable adjustments’ that employers have a duty to make, and the Access to Work programme at the Department for Work and Pensions website (Work and disabled people).

A specialist citizens’ advice bureau, job centre or employment solicitor can provide you with more detailed advice and assistance.

Anyone who has cared for a child will appreciate what a physically demanding task it is. People with Erb’s palsy will find it even more difficult given the limited use of one arm, especially as the child grows.

Women with Erb’s palsy who wish to breastfeed might struggle because they cannot hold the baby to the breast easily (or at all) with their disabled arm. They might also find it difficult to help the baby to latch on. This means that they’ll require assistance to feed their baby, at least until feeding is well established.

Carrying children with the remaining ‘good’ arm can strain one side of the body, causing neck and back problems. Many of our clients feel restricted in the amount of time they can carry their child before it causes pain and discomfort.

Treatment from an osteopath or chiropractor can help ease strains, and a physiotherapist and/or occupational therapist can advise you on techniques for lifting and carrying, as well as exercises to prevent injury.

Toddlers are well known for pushing boundaries and exploring. While manageable within the home, it can prove a real problem if the parent has difficulty in physically restraining or controlling their child in a wider environment. Many people with Erb’s palsy report that they need help when out and about. For these reasons, we frequently allow for the costs of additional professional childcare when pursuing a claim for Erb’s palsy.

Erb’s palsy and brain injury

We are seeing increasing numbers of clients, who have brain injury alongside their erb’s palsy injury. This is because the baby getting stuck, can also result in a period of lack of oxygen and so (usually mild) brain damage.

Given that the brain injury is usually mild, this can be missed initially. It is therefore very important that your legal advisor carefully explores all possible injuries, to ensure that mild brain damage is not overlooked, the symptoms of which may only become apparent when a child starts secondary school and so has to do more for themselves.

Symptoms of mild brain injury can include being slower to process information and so carry out everyday tasks, memory problems, being slower to do things than their siblings eg learning to read, and increased tiredness.

Erb’s Palsy and Mental Health Issues

Sadly many people with erb’s palsy will also experience psychological problems, including difficulties accepting their condition and feeling ‘different’ to their friends, and frustrated about the things they cannot do.

It is very important to tackle psychological issues early on, before they get worse and most claims for erb’s palsy will likely include money for psychological support. You can hear from people with erb’s palsy, and experts, about the psychological impact of erb’s palsy here.

Erb’s Palsy – what about mum?

It is important, in focussing upon a child with erb’s palsy, not to forget that mum may also have been injured during the same birth process – and for mums not to overlook their own possible injury.

Getting the right support for you and your family

If you or your child has experienced a brachial plexus injury at birth, and are now living with Erb’s palsy, you will rightly be asking questions about how this happened. As you will have read above, often Erb’s palsy can be as a result of negligence during childbirth and so you or your child may have a claim for compensation.

Making a claim for compensation can help you and your family to get the support you need for life. Our team of specialist solicitors work with experts in the field of brachial plexus injury, and will build an experienced rehabilitation team around you (or your child) and your family.