Case study

The role of identity in multi-cultural work with families following brain injury

Assimilating, analysing and interrogating the facts of a case, then applying the law is a given for a personal injury lawyer. However, without a deeper understanding of the client’s personal and family identity, my experience is that the individual cannot be adequately represented in a legal claim.

Life-changing injuries have a ‘ripple’ effect on the entire family. Notably, a recent meta-synthesis of qualitative studies on family identity published by Doctors Whiffin and Gracey demonstrates that changed identity due to brain injury is not static. Adopting the imagery of ‘rain on water’, the study suggests that change is dynamic and fluid as all family members adapt to their post-injury lives.

By listening to a client’s personal and family narrative, we better understand their changed sense of identity and needs, and how this should be reflected in the compensation claim.

The nexus between personal and family identity is all the more significant where there are cultural considerations, as illustrated by the experience of a family I have been working with for more than two decades…

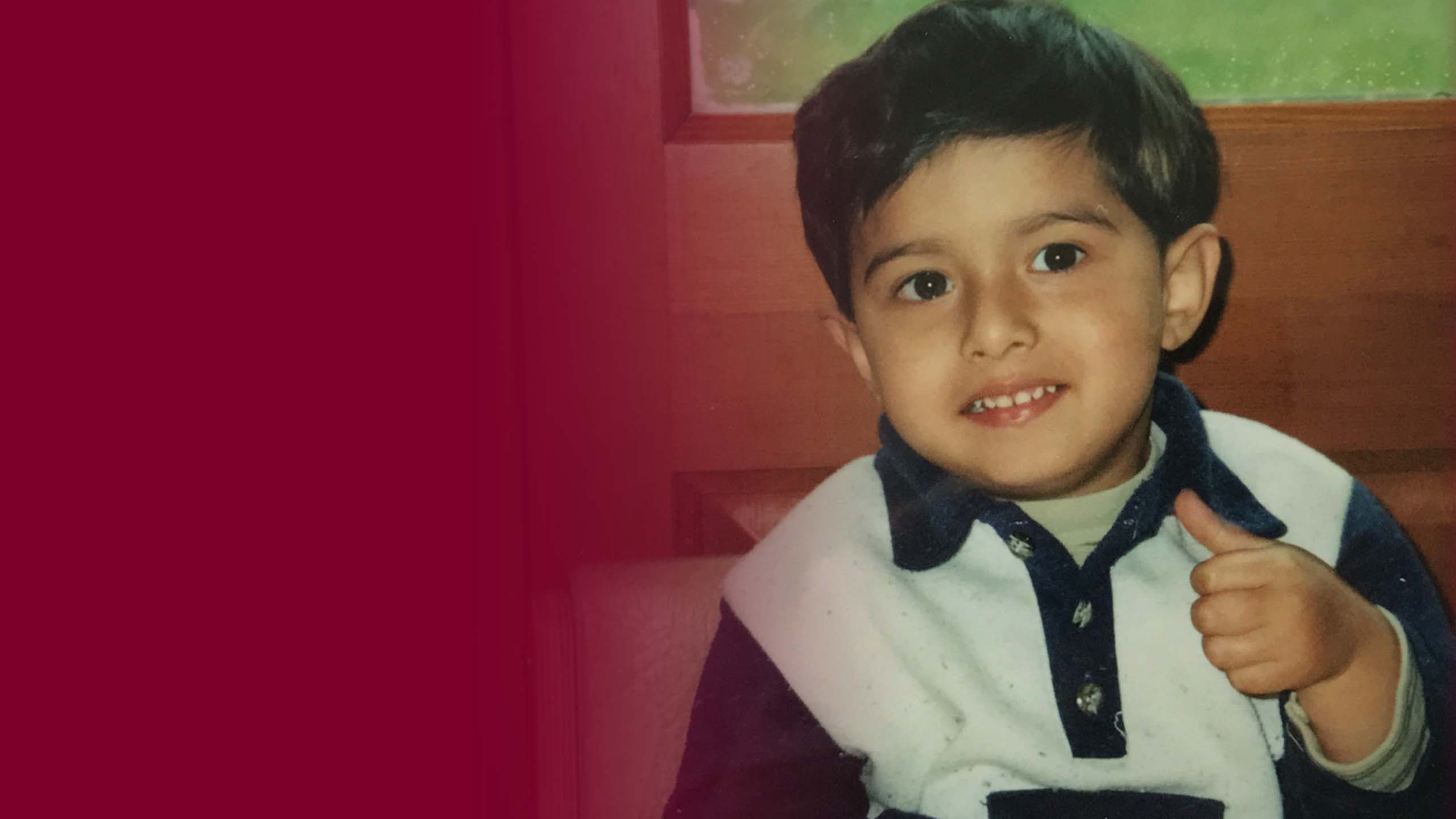

Saeed’s story

Saeed was three years old when, on 4 October 2001, he suffered a catastrophic brain injury while traversing a pelican crossing with his mother and sister. Saeed comes from a Muslim, middle class family who are Pakistan nationals. His father had arrived in the UK on a diplomatic visa in 2000, on leave from a prestigious job in Pakistan to study for a PhD in scientific computing. Saeed, his mother and sister then joined their father in the UK in early 2001. Both parents were unable to drive and Saeed’s mother could not speak English.

Following the road traffic accident Saeed was flown by air ambulance to Southampton PICU where he underwent brain surgery within 48 hours and was in a coma for three weeks. He sustained a right sided hemiplegia, learning difficulties, right gaze palsy, optic atrophy and epilepsy.

In November, Saeed was transferred to a paediatric neurology ward 30 miles from home, requiring a four-hour round trip to visit him. He was subsequently moved to a local hospital until his family successfully campaigned for him to be transferred in January 2002 to The Children’s Trust for rehabilitation. The family were able to stay in a three bed flat close by, resulting in Saeed’s father suspending his PhD research to care for Saeed’s sister. In the meantime Saeed’s mother learnt therapeutic exercises to undertake with him. He was eventually discharged home in May 2002.

I was instructed to pursue a claim against the driver; as a minor who would not gain capacity at 18, Saeed was represented by his father as litigation friend. It was essential for me to understand the family’s religious beliefs, culture and traditions to properly present the claim in the context of UK law. This necessitated an understanding of the jurisdictional and religious differences for the litigation; a journey of mutual discovery as the family were unfamiliar with UK health and legal systems, and I was not conversant with the Muslim faith and Islamic Law.

Learning about the impact of cultural identity on the multi-disciplinary approach

Saeed's parents were therefore catapulted into working with a Multi-Disciplinary Team (MDT), learning new systems while at the same time coming to terms with their son’s catastrophic injury in a foreign country – a huge challenge. For example, her limited command of English created a barrier for Saeed’s mother to confront professionals who were incompatible.

Cultural and religious compatibility was a necessity, highlighted by the poor experience of a case manager who failed to comprehend the family identity and brought his own narrative into the dynamic. Careful selection of professionals was thus critical; indeed the enlightened successor case manager has been so inclusive that she has also been working with the family for over 20 years. Saeed's father was engaged in the medical management, rehabilitation and the interface with the litigation team in his role as litigation friend. Thus the demands on parents created enormous pressures for the family, triggering and sustaining vulnerabilities as they adapted to their new norm.

In March 2003, Saeed's father felt compelled to resign from his studies in order to manage his changed responsibilities: the family thus moved to a private medical treatment visa prohibiting work, compounding their financial difficulties as parents were not entitled to public funds. This meant a complete dependence on the defendant insurer to meet all their financial needs through interim payments. For a man who had always provided for his family this represented a very low point and his GP questioned him about feelings of suicide in 2004.

In conjunction with the MDT we established a team around the client and his family, providing support to help them navigate their changed identity as a consequence of living through trauma and to rediscover and redefine who they were. Saeed's father’s reflections from this period are that it triggered for him the Quranic message of hope and the Islamic framework of daily prayers, promoting optimism for Saeed’s future.

The impact upon the litigation process

In terms of the litigation, I had to investigate whether to claim damages based on compensation in the UK or Pakistan. This required an understanding of the likely reaction to Saeed’s disability in Pakistan.

It soon became clear that Saeed would be treated as a pariah in Pakistani society – an outcast with little or no access to therapeutic and rehabilitation programmes. Parents were thus forced to make a life-changing decision for the family about residency, requiring support from an immigration lawyer (and eventually becoming British citizens thus holding dual nationality).

The claim was defended on the basis that the family would return to Pakistan, in the alternative that there should be no deviation from UK compensation law; accordingly no recognition of the conflict with Islamic Law. To reconcile the conflict of laws we had to rely on the Human Rights Act 1998. More specifically, Article 8 of the Act - the right to respect for private and family life including personal identity – and Article 9 – freedom of thought, belief and religion.

As a legal team we also needed to understand the implications of Shari’ah Law, securing fatwas (expert opinion) from both leading Pakistan and UK Mufti’s. Under Islamic Law there is no distinction between child and parents (regarded as one entity) and all Muslims must be Shari’ah compliant.

Islamic law therefore informed our approach to pleading heads of loss and the mechanism of receiving the compensation. Specifically we took expert advice on Riba (where payment or acceptance of interest is forbidden) and Zakat (a form of almsgiving which is levied at 2.5% on most assets) which is obligatory for all Muslims.

Shari’ah Law also prevents a Muslim taking out a contract of insurance, therefore a periodic payment (annuity) for future losses such as care and case management was not permissible.

Managing the compensation

Saeed’s claim eventually settled at the door of the court for a lump sum, after which I was appointed joint deputy alongside father.

The property and affairs deputy makes every financial decision for Saeed and although joint deputyship is not typical I felt it was appropriate to respect the cultural identity of the family and to avoid counter-transference of my own identity. The Court of Protection honours adherence to Islamic Law if this complies with the Human Rights Act and is in the individual’s best interests - in the context of the lifelong responsibility I considered that a joint appointment was inclusive.

Permission was granted to invest the compensation in a Shari’ah compliant portfolio despite such investments carrying a higher risk and having greater volatility. It took us nearly two years to do so due to the dearth of funds available and the need for enhanced due diligence.

There were many hurdles along the way, including the inability to invest in conventional banks due to the principles of the aforementioned Riba; also Haraam that prohibits investment in forbidden industries such as tobacco, alcohol, selling of arms or drugs; as well as Maisir which prevents investment in gambling.

Saeed is now 23 and continues to live with his family who remain devout Muslims. His father completed his PhD in 2015, his mother is now fluent in English and a competent driver, and his sister has recently graduated from University College, Oxford , securing a job as an assistant psychologist, whilst Saeed’s youngest brother has recently taken his 11+ examination.

We are poised to adapt the adjoining house, to construct a glass link that will enable Saeed to live independently next door to his family. Furthermore we are investigating the purchase of a holiday home in Islamabad which requires us to overcome both jurisdictional issues and a less formal property system, to the satisfaction of the court. This is of huge importance to Saeed and his family to enable them to participate in extended family life in Pakistan.

Finally, we are also scoping out an application to the court for a Statutory Will which complies with the Quranic commandments.

It has been a journey of self-discovery over two decades, requiring me to educate myself on Islamic Law so as not to alienate Saeed’s family. Their enlightenment, openness and generous gifting of an English translation of the Qur’an has enabled me to develop an intimate understanding of their identity and belief systems. Respectful of their culture and etiquette, I avoid organising meetings on a Friday due to Friday prayers, observe Eid and remove my shoes when making house visits (remarkable given my obsession with footwear).

Listening to the family story and being inclusive I believe has led to a better outcome for Saeed; his brain injury was such a disruptor for this family – like ‘rain on water’ – that the respect has strengthened them to weather the storm with a changed but positive future ahead of them. It is a privilege to work with them.

Tracy Norris-Evans is Head of Injury at RWK Goodman.