Scoliosis correction surgery – what are the risks and how can they be mitigated?

Scoliosis is a spinal condition in which the spine curves to the side. It appears mainly in children, and is relatively common. It may remain undetected until children reach the rapid growth phase in adolescence.

Mild cases of scoliosis are often left untreated, while in moderate cases the more conservative approach of bracing may also be utilised. In more severe cases though surgery may be identified as the best course of action, and it is usually undertaken during adolescence.

The most commonly performed surgery is a posterior spinal fusion with instrumentation. The instrumentation rigidly fixes the spine internally through rods being attached to screws, hooks and wires at multiple sites along the curve, with a view to maintaining the corrected position post-operatively while the fusion is completed over a period of months.

What are the main risks of scoliosis surgery?

1. Paraplegia

The most serious risk is paraplegia – loss of movement and feeling in the lower body and legs.

Such a devastating injury as paraplegia can arise through a number of different mechanisms. These include ischaemic injury due to a systemic problem with oxygen delivery, ischaemic injury due to damage to the arteries, or a direct traumatic injury to the spinal cord. Sometimes these causes may even combine.

The anterior spinal artery is supplied by a number of “feeder” arteries which arise from the aorta, the largest of which is the artery of Adamkiewicz. These arteries are vulnerable to distortion during straightening of the spine, or to direct injury during instrumentation. In addition, the anterior spinal artery is itself vulnerable to compression or distortion during manipulation of the spine or during instrumentation.

A more direct mechanism injury to the spinal cord itself can occur due to stretch or compression as the spine is manipulated, or in association with the use of instruments within the vulnerable area. Any injury to the arteries or to the spinal cord itself will be amplified by levels of systemic hypotension and anaemia.

2. Blood loss

That brings me on to the next major risk of scoliosis surgery: excessive blood loss. There is a lot of muscle stripping and exposed area during the surgery, which leads to blood loss.

With proper technique, blood loss can usually be kept to a reasonable amount and blood transfusions are rarely needed, but blood loss leads to hypotension and anaemia, which can be contributory causes to catastrophic spinal cord injury. It is therefore very important to monitor blood loss and blood pressure throughout the procedure.

3. Other risks

Other risks of scoliosis surgery include failure of the spine to fuse, infection, cerebrospinal fluid leak, and instrumentation failure.

Sometimes there is a failure to achieve a significant reduction in the degree of curvature, and this may be because the operation has been performed at the wrong level. If, for example, the instrumentation does not extend low enough into the lumbar spine, this may lead to an inadequate correction. Equally, if the instrumentation is too long, it may cause ongoing pain for the patient; for example, the rods may impinge on to the facet joints, causing pain. In addition, misplaced pedicle screws can cause significant ongoing pain.

How can the risks be mitigated or managed?

There are a number of important safeguarding mechanisms which can and should be used during scoliosis surgery.

1. Reducing the risk of paralysis

To reduce the risk of paralysis, the spinal cord is monitored during surgery with several simultaneous methods.

The first method is somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEPs), which are electrical signals created by stimulation to the peripheral nerves. The signals should remain constant throughout the surgery, and if they begin to slow at any point, this can indicate compromise to the spinal cord or its blood supply.

The second method is motor evoked potentials (MEPs), which are similar to SSEPs, but which monitor electrical signals from muscles rather than nerves.

MEPs and SSEPs are used together in the course of scoliosis correction surgery, with the aim of monitoring the anterior and posterior spinal cord. If only one of the modalities is used, it risks missing any damage to the spinal cord not being monitored, since SSEPs effectively monitor the posterior spinal cord, and MEPs more effectively monitor the anterior spinal cord.

Prior to the use of SSEPs and MEPs, the Stagnara wake-up test was commonly used. This involved waking the patient during the surgery and asking them to move their feet. Due to improvements in the electrical monitoring methods, the wake-up test is now rarely used.

The purpose of these tests is to provide an “early warning signal” of any spinal cord complication. If too much compression, or too much loss of blood, is compromising the spinal cord, the surgery can be stopped and the surgical team can instead concentrate on restoring as much of the spinal cord’s health as is possible.

Find out more about reducing the risk of paralysis through neuromonitoring here >

2. Reducing the risk of excessive blood loss

It is obviously also vital to accurately measure blood loss and blood pressure throughout the procedure, as hypotension significantly increases the risk of spinal cord injury.

Following surgery, it is important to ensure that the patient has normal sensation as soon as possible, as if the spinal cord has been damaged or compromised, remedial surgery (in the first instance to remove the metalwork) will be required urgently to maximise the chances of recovery or at least some improvement in function.

3. Reducing the risk of other complications

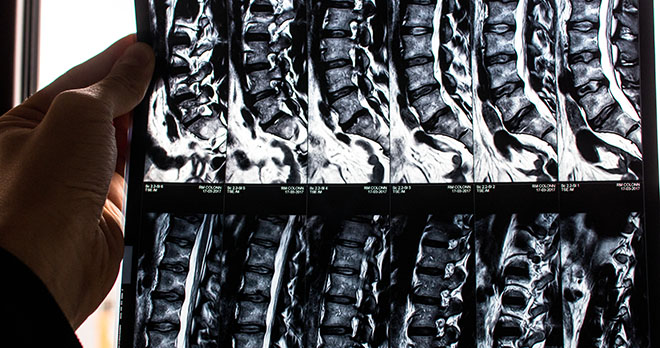

In terms of avoiding some of the lesser (but still important) risks, such as not achieving the required improvement in the curvature, scans and x-rays (pre-operative, peri-operative and post-operative) are every important.

Pre-operatively, MRI is required to exclude any unrecognised congenital spinal abnormalities which may increase the risks of correction. In addition, “bending x-rays” should be performed, to assess flexibility and therefore allow pre-operative planning for screw placement. During the procedure, “balancing x-rays” should be carried out, to ensure that the shoulders remain parallel to the pelvis, and the head is centred above the pelvis.

Post-operative x-rays should also be performed to check the extent to which the curvature has been corrected, and the alignment issues mentioned above. Post-operative scans should also detect any misplaced pedicle screws.

When might a claim arise for negligent scoliosis surgery?

Clearly patients consent to some risks when undergoing spinal surgery, and the risks consented to include paralysis or less than satisfactory correction of the scoliosis, for example.

In the event of a poor outcome, however, patients may be able to bring a successful claim if not all steps have been taken to safeguard them by minimising risk. For example, it will be argued to be sub-standard care to proceed with a scoliosis correction procedure in the absence of MEP and SSEP monitoring, or if that monitoring is not working properly. At the very least, in those circumstances, the operating team should revert to a Stagnara “wake-up test” following placement of the instrumentation. Failure to adequately monitor blood loss and blood pressure, creating dangerous hypotension, could also form the basis of a claim in the event of damage to the spinal cord.

In terms of consent to treatment, it might well be successfully argued that a patient has only consented to the operation proceeding if the promised monitoring is available, utilised, and is working effectively, and that consent might be considered impaired by the absence of effective monitoring.

In the event of an inadequate correction of curvature, if the surgeon cannot demonstrate that all appropriate imaging was carried out before, during and after the operation, he may well find it hard to defend a claim for negligence. Instrumentation which is too short, failing to achieve the desired correction, may found a successful claim, as may instrumentation which is too long and impinges painfully on other structures, and misplaced pedicle screws, if they cause damage or pain.

As experienced medical negligence solicitors we have brought claims for negligent spinal surgery for many clients, including for negligent surgical treatment of scoliosis.

We would encourage anyone who thinks they may have experienced negligent treatment to contact us for a free consultation on whether they have a claim.

Find out more about Simon's expertise

Contact our enquiries team to find out more about making a claim for scoliosis surgery negligence

Call now