Lacking clinical evidence and causing injury – the ever-growing case against mesh implants

The use of a mesh in order to treat hernias has recently come under scrutiny. Concerns have been raised that a number of these meshes are being used across the NHS without serious consideration or reasonable clinical evidence about the potential long-term effects for patients.

The new data was obtained by the BBC’s Victoria Derbyshire programme following a Freedom of Information request, and shows that more than 100 different types of mesh were purchased by NHS Trusts from 2012-2018 in England and Scotland. In that time, there have been around 570,000 surgical meshes fitted in England, with some surgeons quoting the complication rate to be 12-30%.

The data demonstrates that the extent to which some meshes are tested can be incredibly limited. In some cases the devices have only been tested on animals, and even then the mesh has only been implanted and left in place for a few days. These tests fail to consider if the subject is experiencing pain; and this is a known complication of surgical meshes. This has led to some doctors describing the tests currently being used as “completely inadequate”, and has encouraged calls for the NHS to stop using meshes that have not been subject to proper testing.

Another concerning issue is the fact that a new surgical mesh can be approved for use purely on the basis that it is similar to another product that is currently in use. These older products themselves have not had to undergo any rigorous testing or clinical trials to assess their safety.

Many patients who spoke to the Victoria Derbyshire programme had been told that “no trained removal surgeons” were accessible to them when complications occurred.

So, why is mesh used?

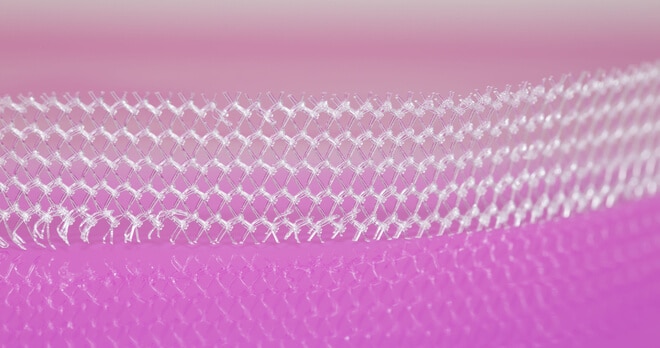

Surgical meshes – widely used since the 1970s – are most commonly used in order to treat hernias in the abdominal-cavity, those caused by incompletely healed wounds, and umbilical hernias.

When someone suffers from a hernia, part of an organ will protrude and break through the muscular wall that keeps it in place; for example the intestines may break through a weakened area in the abdominal wall. The mesh will be applied to the weakened area and the surgeon will sew the hole closed and patch the hole with the mesh. This mesh acts as a replacement for the broken tissue. The intention is that the mesh will then hold the protrusion back into place.

Once the mesh is applied to the site of the protrusion, it is intended to stay there permanently.

Unfortunately, a serious complication that patients can suffer after having a mesh fitted is the migration of the mesh device. This occurs when the mesh used to treat a patient’s hernia moves from its original location. Migration often occurs because either it was inadequately secured to surrounding tissue, or because the presence of the mesh causes the body to have an inflammatory reaction. In this latter instance, the mesh erodes before it migrates, and this can make it more difficult to find and extract as it will shrink in size. In both instances the mesh moves out of place meaning that there is a risk of the hernia reoccurring, and removal surgery is required. This raises additional concerns when we consider that so few surgeons can remove a faulty mesh device.

How is the issue being addressed?

Currently the use of a vaginal mesh is suspended for most women in England pending a government review. Lady Cumberlege, who is heading up the review, has suggested that any recommendations that are made in relation to the use of vaginal meshes will also be relevant to the surgical meshes used to treat hernias.

What is more, in Scotland no vaginal mesh implants have been carried out since their use was halted in 2018. However the current bans on the use of vaginal meshes do not concern the meshes being more widely used in instances concerning hernias.

Graeme Tunbridge, the director of devices for the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), which is a government agency responsible for ensuring that medicines and medical devices are safe, has also admitted that the issues surrounding surgical meshes do “need strengthening”. He has suggested that new legislation on the matter will follow on from the government review and take effect from May 2020.

Mr Tunbridge’s position seems to match that of the Royal College of Surgeons for England, who have called for “all implantable devices to be registered and tracked to monitor efficacy and patient safety in the long term.”

It is clear that there needs to be greater regulation when it comes to the types of surgical mesh that can be used. What is more, the clinical testing for these meshes has to be a lot stricter.

As it stands, a significant number of people are possibly at risk of serious injury if they undergo hernia treatment that involves a surgical mesh. Whilst resolutions to this issue may not be immediate, they are possibly on the horizon. Hopefully they will be adopted soon.